I’m lucky enough to get to tour some outstanding real homes through my work – and in doing so speak to some inspiring self-builders and renovators who’ve gone the extra mile to design and realise their dream property.

So I was intrigued when oak frame specialists, Oakwrights invited me to spend the night at their Woodhouse show home in Kenchester, just outside Hereford.

It may not be a self-build in the strictest sense, but it’s surely a very close second. Add to that my natural fascination with oak frame, as a trained site carpenter and hobbying furniture maker, and this was an opportunity I couldn’t refuse!

In many ways, Woodhouse represents the final piece of the project-planning puzzle. No matter how much research self-builders do (and in my experience it’s a huge amount), when it comes down to it we have to put a lot of faith in our architect or house designer. Even with the advent of easy-to-use 3D software like Google Sketchup, it’s difficult for us uninitiated folk to envisage what it will be like to live in a house once the work’s done and dusted – and how the architecture will truly look in situ.

A number of the UK’s larger design and build companies have properties near their HQs that you can visit, allowing you to touch and feel the materials they use. Some – including Oakwrights – also have happy customers who are willing to open their doors a couple of times a year to let potential customers look around. Seeing a finished project in the flesh gives you a warts-and-all perspective that could just change your mind about what you do and don’t want out of your new home.

What makes the Woodhouse special is that you can experience it for real at your own pace – and at different times of the day. You don’t just have to imagine what it would be like to slip into the garden for a balmy summer evening’s drink; or to wake up to sunlight streaming in through the glazed gable in your bedroom. You’ll literally be there to soak it all in and find out first-hand what works for you.

It also gives you a sense of what Oakwrights is able to achieve for self-builders. Designed and built by the team, it exemplifies why the company is so keen to encourage its customers to use their services from start to finish. “More and more self-builders are going for our whole package, following the entire build from architectural design through to raising the frame and wrapping the house with one of our encapsulation systems,” says Michael Connolly, the company’s marketing manager, who estimates that around 40% of Oakwright’s projects now follow this route.

A contemporary country home

So how does Woodhouse match up to the tailor-made readers’ homes I’ve had the privilege to explore over the past decade or so?

Well it definitely has the wow factor that so many self-builders aspire to achieve. As I pulled up outside the house (which true-to-form the Satnav thought was still about two miles away), dusk was closing in. Set back from the road on its relatively compact plot, Woodhouse looked incredible.

It was built in 2006, so it’s had nearly a decade to weather handsomely into the surroundings. The original timber cladding has taken on a slightly silvery hue that feels suitably rustic, for example. But unsurprisingly it’s the oak frame that takes centre stage – with the internal beamwork visible from outside through the extensive glazing to add even more depth to the characterful-yet-contemporary architecture.

Everyone’s plot is different; and everybody has different tastes – so I don’t think Oakwrights set out to create the perfect home here. What they have done, though, is to show off with aplomb some of the amazing features that can be achieved with post and beam and to explore the materials that truly complement an oak frame building – such as characterful clay tiles, solid wood doors and natural stone floors. Cleverly, the team has also discretely blended these elements with the kind of modern touches and technologies that many self-builders would love to give a trial run before fitting them in their own homes. And it’s all tied up into a place that feels like it could be your home, with just a few tweaks here and there to suit your lifestyle.

Take the master bedroom, for example. This has to be one of the most amazing rooms I’ve ever stayed in – with beautiful oak beams rising right up into the vaulted ceiling. The 46m2 space features floor-to-ceiling glazing that takes in the garden before opening up to a wonderful vista of the surrounding countryside. Its south-westerly aspect means that it captures most of its sun in the afternoon and evening (when you may want to open up the Juliette balcony); but the surprise for me was that it delivered just the right amount of morning sunshine to make for a great start to the day.

If a light-filled morning isn’t your cup of tea (to be honest it’s the only way I can be even vaguely alert earlier than 9am!) then try staying in the second bedroom instead, which is still plenty big enough for most homeowners. With much smaller windows and a north-easterly aspect, it has a very different vibe – but still plenty of charm. Its ensuite is neatly tucked into an eaves space that demonstrates how effectively you can make use of an oak build’s nooks and crannies.

Downstairs, the main part of the house is an open-plan living space. Approach through the garden and you get the full effect of the spacious ground floor plan, glimpsed first through the glazed walls. Step inside and the hallway, with its travertine flooring, stretches out in front of you – the eye drawn up to a gorgeous contemporary staircase at the far end. To the right is the kitchen-diner, decked with solid wood floors and kitted out with timber furniture, while to the left is the sitting room complete with woodburning stove and chunky oak mantel.

At the rear of the house is a utility-kitchen and downstairs WC. The adjoining garage turns out to be a haven for timber frame geeks – with demonstration panels of Oakwrights’ three wall encapsulation panels (Wrightwall Natural, Wrightwall Light and the 3I Infill).

In fact, the whole house is a bit of a treasure trove. Open up some of the cabinets in the utility area, for example, and you can sneak a peek at the nuts-and-bolts of this house – including the water-based underfloor heating (UFH). With both timber and travertine floors throughout what’s already a cosy house, you can feel how UFH might work in tandem with different coverings in your own project. Each room’s lighting scheme offers multiple moods, too, easily accessed using simple wall switches. You can try out bells-and-whistles features such as the invigorating body jet shower or the electric Aga, too.

What goes into an oak frame?

With my carpenter’s hat on, it’s difficult not to be taken with the natural beauty of an oak frame building. Oakwright’s approach combines the wood’s innate charm (think warming grains, characterful cracks and all the imperfections that give oak its unique appearance) with modern technology and the craftsman’s touch. When you see the carpenter’s marks on the frame, notched to ensure everything’s assembled in the right order on site, you can feel the artistry and personality that goes into this kind of building.

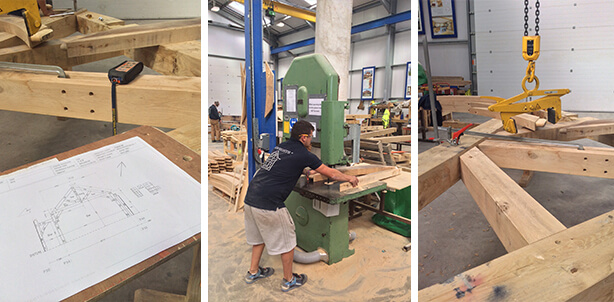

Oakwrights builds around 75 homes every year across the UK, and the company’s state-of-the-art production lines are located just a few miles from the Woodhouse – so serious self-builders will always make the trip to see how their project might be put together. Feeling bright and breezy after a great night’s sleep at the show home, I checked out the factory with marketing manager, Michael Connolly and production manager John Lloyd.

“We source most of timber from France; the best quality oak comes from the central south part of the country,” says John. “But some comes from Germany and a little is from England.” The grade of the wood largely depends on which sawmill it comes from – so the team chooses the right supplier depending on the span the beams need to cover. “A 6m span is pretty standard, but we can reach 10m or more at the top end,” explains John. “All the wood arrives in bespoke-cut by the sawmill.”

The timber is checked in-house by qualified graders before it goes through the production line; first up is the planer, which is designed to float as it cuts to cope with the beams’ natural curves. “Accuracy is vital for the computer-aided CNC system we use, but planing is also a great way to show the grain – and is much easier than rough sawing,” says John.

Once it’s dimensioned, the oak’s fed into the heart of Oakwrights’ operation – the Hundegger K2i. This is a spectacular piece of kit, controlled by a CAD software package that translates bespoke house plans into precisely-cut timbers to make the oak frame kit. John demonstrates how it works with a replacement brace for one of the project’s that’s being test-assembled in the framing shed nextdoor.

The beams arrive cut to size and ready-sequenced, so the Hundegger can work quickly and accurately to carve out the most complex part of the process: the joints. The brace John runs through needs a chamfered tenon cut at both ends – and the K2i gets the job done in about 30 seconds. I’ve never worked a piece of oak that large before, but I can imagine each tenon would take me at least half an hour to cut by hand; and I doubt I could match the level of accuracy.

The Hundegger gets through about 60m3 of oak each week. “The average house has about 20m3 of oak,” explains John, “so not many manufacturers match our output.” With the posts and beams ready-to-go, the next step is to dry-fit them in the framing workshop – which most customers will visit before they sign up with Oakwrights.

“At this point, our craftsmen test-assemble the frame using temporary metal pegs,” says John (oak pegs are used in the final iteration). It’s much easier to identify and solve any problems now than wait until the project’s on site and have to re-order posts or beams. The team will also do any tricky work at this stage, such as cutting curves into braces – so there’s still a large element of hand finishing. “We encourage our craftsmen to take ownership of the project from here,” says John. “They’ll often go on site, too – it’s good for them to get that variety, and as they know the project inside-out they can respond to any issues quickly.”

The complete package

The final leg of my visit was at the encapsulation factory – where Oakwrights produces the wall and roof panels that either wrap around or infill the oak frame (depending on the spec you choose).

Encapsulation manager Alex Edey led me round the workshop, where the team was busily working on a storey-height panel. “We use a pair of Weinmann butterfly tables that hold the panels in place, allowing us to work on them,” he explains. The two wings rise up and clamp the units together for perfect accuracy – which helps to ensure good air tightness.

The Wrightwall Natural panels are then filled with Warmcel insulation using an X-Floc machine, which the team affectionately refers to as ‘the Tardis’. “We know the exact volume of each panel and that the Warmcel weighs 70kg per m3, so we can pump the closed cavities to achieve a perfect fill,” says Alex. The team can create panels up to 8m wide and 3.8m tall, but most of their output is 2.4m tall so it’s tailored to storey-height.

And tailoring is the key with Oakwrights’ encapsulation systems. “When people come to us, they often compare what we offer with structural insulated panels (SIPs), but the two couldn’t be more different,” says Alex. “Our panel designers were oak frame designers before this, so they understand the whole process and package – including crucial things like the differential movement that occurs between the frame and panels.”

There’s close attention to detail, too – eaves and verges follow standardised processes, wall studs and roof battens are all at 600mm centres and dormer windows are often prefabricated rather than being site built, for example. All of which helps to increase build speeds, underpin quality, reduce labour and minimise unexpected costs on site. “With most homes, the frame is completed in around a week and the encapsulation a further two weeks,” says Alex.

The synergy of the whole package – emphasised by the fact that the architectural team’s office is literally next door – underpins Oakwrights’ philosophy when it comes to designing and building bespoke homes. And that brings us neatly back to the Woodhouse, a contemporary country home that feels as relevant to modern living today as it did when it the frame was first raised eight years ago. If you’re serious about self-building an oak frame home, you won’t regret a visit.

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later