Can An Old Building Be Eco Friendly?

Old buildings tend to get a bad press when it comes to energy efficiency; they are typically considered to be cold, draughty and hard to heat. This is not really accurate – in fact, old homes generally outperform their mid-20th-century counterparts.

Part of the problem is that the methods used for Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) and Green Deal assessments do not model the complex structures of old dwellings very well. In-situ measurements made in actual period houses consistently demonstrate that they are more efficient than the ratings would lead you to believe.

Having said that, most old buildings will need some upgrading to bring them up to modern expectations of comfort and efficiency. Many will have suffered from poor maintenance or inappropriate interventions in the past and will require some remedial work to improve their performance.

Almost all can be brought up to a reasonable level, but we have to accept that they will never match a modern, airtight, highly insulated building.

Damp in period homes

The first and most important step is to make sure that the fabric of the home is dry. Apart from potential damage caused to the health of both building and occupants, damp walls conduct heat and make a house colder.

The most common causes of damp are faulty rainwater goods and inappropriate, non-breathable plasters, renders and paints. If any of these issues exist, they must be resolved first to enable a dry structure, otherwise any other improvements will be largely wasted.

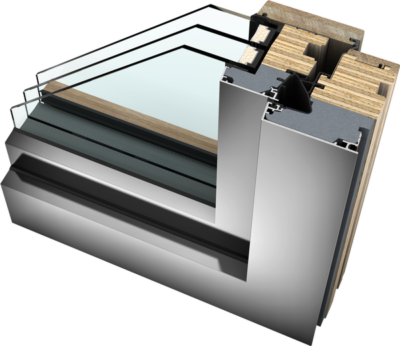

Efficient windows & doors

A prime reason for poor thermal performance, windows and doors lose heat directly through features such as single glazing. There are also problems as a result of draughts around casements, sashes and doors, and even through letterboxes.

Double glazing is often deemed inappropriate for old houses, especially for sash windows, and in any case is unlikely to be allowed if the building is listed. However, a combination of draught-stripping (even sash windows can be upgraded very effectively), secondary glazing, insulated curtains or blinds and shutters, if appropriate, can make old units perform as well as modern double-glazed fixtures.

Reducing air infiltration

Experts are becoming increasingly aware that air movement in a building has a much greater effect on comfort than the actual temperature. Cold draughts will make occupants feel chilly, regardless of a room’s temperature. Some old buildings suffer from poor airtightness, even after improvements have been made to the windows and doors.

Gaps around infill panels in timber frames or between the boards of suspended floors can generate considerable draughts, while unused chimney stacks allow very large volumes of warm air to escape.

Improving air tightness can make a disproportionate improvement to how warm a house feels. It is important not to go too far, though. A traditionally constructed dwelling needs to maintain a good degree of ventilation to ensure that the fabric of the building can still breathe.

If it was to be made completely airtight, walls would trap moisture and become damp and cold, defeating the improvements made elsewhere. In particular, chimneys must never be completely blocked – a little airflow is essential to avoid problems.

Temperature buffering

As well as assisting with the breathability of the fabric and helping to keep walls dry and warm, lime and clay plasters have a direct influence on room temperature and comfort. As they periodically absorb and release water vapour from the air, they buffer the room temperature through latent heat effects. A room that feels cold with modern plaster will seem warmer, simply as a result of replastering using lime or clay.

This room has been replastered using lime, a breathable material that will make the atmosphere feel much warmer and more comfortable

Insulation: quick wins

A large proportion of a house’s heat is lost through the roof. Loft insulation is usually no more difficult to install in an old building than a modern one, and significant energy savings can be made with very little expense or disturbance to the fabric.

You must be careful not to create new problems, though. Insulation will obviously lower the temperature in the roof space, and this can lead to an increase in relative humidity, creating the risk of condensation, which can cause mould growth or even decay of roof timbers.

To avoid this, natural, hygroscopic insulation materials such as hemp, sheepswool, cellulose or wood-fibre should be used and the ventilation of the roof space must be maintained. It’s particularly important not to block eaves ventilation with the insulation material.

Suspended timber floors can also often be insulated. If the floor can be lifted without causing any damage, products can be fitted between the joists, supported in pockets formed by an airtight membrane. This has the benefit of eliminating draughts between the boards as well as giving an improved thermal performance. Because the floor is the part of the house with which you are almost always in contact, upgrading it can make a big difference to comfort levels.

Solid wall insulation for old houses

Almost all buildings dating from before about 1919 have solid (rather than cavity) walls, and much attention is currently being directed towards insulating them – it’s almost always recommended in an EPC or Green Deal assessment, for example. Unfortunately it is less straightforward than this would suggest.

One problem is that the starting point for considering insulation is almost always flawed. For anything thicker or more complicated than a 230mm-deep brick wall, the assumed existing thermal performance will be worse than it really is. As well as this, the predicted performance of an insulated wall has been consistently shown to be more optimistic than is actually achieved.

As a result of these and other complex factors, real energy savings are regularly found to be much lower than predicted. Because this is a very expensive process, true payback time will be so long that solid wall insulation may not make financial sense.

More serious, however, is the potential effect of insulation on the performance of the wall. The physics involved are so complicated that we cannot predict outcomes with any confidence. There are serious risks of condensation within the fabric of the wall and interference with the equilibrium of breathability.

At worst this can cause mould growth, which is dangerous to the health of occupants, and damp, which will damage the building fabric and tends to make the wall colder. So it is possible that the insulated wall could eventually be colder than when it was uninsulated.

In some instances, limited solid-wall insulation may be justified, but it should only be carried out with the advice of an expert with detailed knowledge of traditional buildings.

Photo (top): Cellulose insulation laid on a membrane between the joists of a suspended timber floor

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.