Water Saving Systems: Rainwater Harvesting, Greywater & Blackwater

One thing this country doesn’t seem short of is rain, but the frequency of water shortages over the summer months, coupled with an increased environmental awareness, means it makes good sense to conserve and reuse water, even here. All mains water in the UK is treated and cleaned until it is fit for drinking, which uses a considerable amount of energy, yet only a tiny percentage of household water consumption is actually for drinking.

Thinking about it like that, using mains water for jobs such as flushing the toilet, washing clothes and watering the garden suddenly seems extremely wasteful. But what can you do? Well, simply taking measures to recycle and reuse water can easily save the country water and energy, and save you money.

Rainwater

Those of a ‘you-don’t-get-anything-for-free’ mindset will be glad to hear there’s one commodity available that won’t cost you a penny – rainwater. The large amount of rain that falls in the UK every month can be used all around the home and garden, reducing the amount of mains water your home consumes and, if you’re on a meter, pay for. No matter how much you use, no one will charge you for it or attempt to legislate it.

One of the simplest ways of collecting and using rainwater, known more formally as ‘rainwater harvesting’, is just using a butt or old-fashioned barrel placed underneath a gutter down-pipe. You can easily use this water for washing the car and watering your plants, and you can pick up water butts relatively cheaply – from as little as £20.

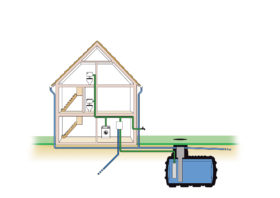

A rainwater harvesting system is a step up from a water butt but works with the same principle. Water is collected from a down-pipe into a receptacle, then filtered into a tank through a mesh to separate any leaves and debris. The tank can be located above or below ground. With a pump and some clever plumbing the water can be used to supply dishwashers, washing machines and to flush the toilet. An added benefit for washing machines is that rainwater is extremely soft and won’t cause any limescale build up.

With some experience in plumbing and drainage, you can install a technically advanced system yourself. But if you want something state-of-the-art, including a butt, underground storage tank and large pump, consider calling the professionals.

Cost will depend on the type of system you opt for, but an average rainwater harvesting kit can be expected to go for anything from £800 to £3,000. It’s worth bearing in mind that they have a relatively short payback period, depending on your water utility charges and use, as systems can cater for around half of household water usage, therefore saving up to 50 per cent on bills.

Rainwater harvesting kits are usually installed during the building stage of a new property or extension, as at this stage the tank and piping can be incorporated easily and at a low cost. Retrofitting a system could be slightly more disruptive, as any copper piping may need to be replaced and a hole dug for the tank if you want it underground. When installing a rainwater harvesting system, you need to ensure that you comply with the standard Building Regulations for digging, but planning permission should not be required.

Greywater

Wastewater from sources such as showers, baths and washing machines – but not toilets – is known as greywater. As it usually contains residues from soap and detergents, so while slightly contaminated, it’s not extremely dirty. Greywater is not fit for drinking, but it can be put to other uses around the home and garden in its raw form, or treated and then recycled. Washing-up water is not suitable for reuse, as it contains too much grease.

Reusing greywater can be very simple if you are happy to use the water directly without treatment, but this is really only suitable for garden purposes. To do this, all you need is a diverter valve attached to your drainpipe and a storage vessel such as a butt. A diverter will give you a choice of whether to send water straight down the drain or to send it to storage, depending on how contaminated it is. This option is very important, since there are times when harmful household cleaning products, such as bleach, are washed down the plughole, which you wouldn’t want to use on the garden.

Once collected, it’s best to use the water as soon as possible, as it may go rancid and start to smell if stored for too long. If you do plan on reusing water in this way, consider changing and minimising the cleaning products and toiletries you use, perhaps opting for eco-friendly versions.

Greywater recycling systems collect water, treat it and reuse it for purposes other than drinking, such as to flush toilets and even feed washing machines. A typical system collects it in a tank, and then passes it through a filter to remove any solids. The water is then disinfected with a little chlorine, after which an electric pump or aerator can oxygenate the water before use.

Before you commit to installing of a greywater recycling system, you need to assess if it will be beneficial to you. Compare how much greywater you are likely to generate with your demand for water – the higher your demand, the better suited you are. Greywater recycling could save a third of domestic mains water usage and, as with rainwater harvesting, if your property is metered, this will reduce your water bill. Your financial savings will depend both on the price of water in your area and the volume you reuse.

Unfortunately, greywater recycling systems don’t come cheap, and the payback periods can be lengthy. A basic system will cost you in excess of £3,000 – without installation. It’s worth noting that, as with rainwater harvesting, installing systems in new buildings should be more cost-effective than retrofitting.

Blackwater

Although most UK homes are connected to mains sewers, some aren’t, sometimes by choice. For unconnected homes, the most common method of treating effluent, or blackwater, is to use a septic tank and some form of secondary treatment. There are a number of secondary treatment options used in the UK and more widely in the rest of Europe, such as reed beds, ponds and septic drain fields. The most efficient type of secondary treatment will vary from home to home, and will depend not only on the size of a house and family, but also on soil quality, proximity to a watercourse and even rainfall.

Using reed beds for sewage treatment has become more popular in the UK over recent years, and it’s now possible to build such a treatment system in your back garden. In general terms, the effluent from a septic tank (or similar) is filtered through a tank or pond area containing layers of sand and gravel planted over with reeds. The reeds provide bacteria with the ideal conditions and temperature in which to break down pollutants and nitrogen in the effluent. The resulting water should be pure enough to safely discharge into the environment via a watercourse – which could be a large pond or nearby stream.

The reed bed itself needs to be carefully designed and planted by experts, and the waterflow through it should be monitored well. It is worth bearing in mind that systems like these do take time to plant on and grow, and are therefore a long-term commitment. Also, it’s a good idea to discuss your plans with your neighbours, as reed beds are most efficient on a larger scale, and could be used by an entire community.

Arguably, a reed beds system in your garden would not need planning permission, as it could be part of your permitted development – a pool used for a purpose incidental to the house. This would not apply, however, if the house were listed, or if the reed bed more than 10m2 and more than 20m from the house. Regulations will differ if you live in a national park, on the Norfolk Broads, or on a World Heritage Site. In all cases, if the reed bed is outside your garden, it would require permission. Before any decisions are made on a project like this, you should discuss your plans with the local council.

Another option is a pond, which works in a similar way as a reed bed by using plants and bacteria to break down and neutralise harmful nitrates in effluent. They can be seeded with a variety of aquatic plants and can look very attractive. The downside of a pond is that you need a large surface area for it to work successfully – at least 50-100m2 – for which you would definitely need planning permission. So, unless you are building one for a community scheme, you may want to look for another option.

Septic drain fields, or leach fields, are popular in the US, and the treatment techniques are beginning to emerge in the UK. They operate through perforated pipes, buried in deep trenches, which allow the liquid to leak out into the surrounding soil, which in turn absorbs the waste. The design of the field – which depends on the size your home and the soil conditions in your area – can be costly and may require an engineer or licensed designer. When done properly, they do provide an effective and low-maintenance treatment, but if done poorly, the overflow effects could be hideous in wet weather.

For a completely different option, composting toilets are making a comeback. They collect waste and transfer it to a sealed container where an anaerobic biological process involving bacteria, fungi and other organisms destroys harmful pathogens in the effluent, transforming the waste nutrients into fertile soil, and reducing health and environmental risks. There are hundreds of different composting toilets, ranging from simple DIY designs to high-tech commercial models. Typically, you should expect to pay from £500 to £1000.

Main image: Polypipe’s Rainstream system uses an electronic control system to monitor water demand pump it to the required outlet

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.