Use code BUILD for 20% off

Book here!

Use code BUILD for 20% off

Book here!Regional geology has had a key role to play in shaping Britain’s housing stock – both in terms of style and substance. In the first of this series on vernacular design, I’ll be looking at what’s influenced traditional architecture in the north of England.

For the purposes of these articles, I’ll be linking several counties together to form mini regions that share many common architectural traits. These areas don’t necessarily correspond with the terms we’d traditionally use to describe different regions.

Vernacular design: the basicsAlthough we’re part of a relatively small land mass, our geology varies widely. As you move across the UK, the rock type and nature of the land changes. This is reflected in each region’s building materials, design and construction methods – sometimes quite subtly, sometimes rather more dramatically. The character and personality of houses built in the past sprang directly from the need to use locally-available materials. There were other influences, too, with social and economic factors (such as the industrial revolution and technological developments) coming into play. This article gives you a general insight into local styles, but do bear in mind they can’t be divided into clearly-defined areas as different regions do merge into one another. |

For example, we’d usually refer to Cheshire as being in the North West – but in terms of its local geology and vernacular styles, it’s more in tune with some of the West Midlands counties.

In this article, I’m looking at Cumbria, Northumberland, County Durham, Derbyshire, Lancashire & Yorkshire.

The hills and valleys of the Lakeland area provide a dramatic backdrop to its traditional rural buildings. This is a distinct geological area, made up of hard mineral-bearing slate and large areas of volcanic rocks, which together form the vast dome of the Lake District.

The rivers radiate out from the centre of this dome, forming very steep valleys that were quite isolated before modern methods of travel were available. In spite of this, the building style is consistent throughout the area.

The more accessible areas have long since been developed for tourism, with many of the original buildings becoming the victims of ‘tarting-up’ by the Victorians, who had overly-romantic ideas about the ideal architecture for a lakeside setting. They added a variety of verges, shutters, verandas and complex roof shapes, all of which are the exact opposite of the genuine traditional buildings, which are more sombre in character, occasionally enlivened by some unusual architectural features. There are a few original cottages left, but most of the surviving older buildings are farmhouses.

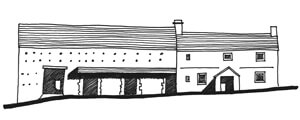

This sketch shows a Cumbrian barn with pentice – an overhanging roof that shelters the area beside the doorway

This sketch shows a Cumbrian barn with pentice – an overhanging roof that shelters the area beside the doorway

The inhabited farm buildings were often whitewashed, with the more functional barns and outbuildings left as unfinished stone. The preferred layout was the longhouse, with the house, byre and barn in a continuous terrace under the same roof, although sometimes the barn is taller than the others. A common local feature is the ‘pentice’, a shelf-like roof that provides shelter to the area outside the barn and byre doorways.

The slate-like walling stone can be split into long thin pieces with the mortar joint recessed, emphasising the shape of the dark blue-grey or brown blocks. The district’s pale blue-green Westmorland slate has been used for roofing throughout England but could sometimes be found in large pieces here, so was often used for lintels and corner-stones. Roofing slates were laid in diminishing courses, which means that very small courses were used at gutter level, with the size increasing up towards the ridge.

Apart from giving a pleasing appearance, this method was also economical as it allowed all sizes of slate to be used. The roofs are very simple shapes without any hips or dormers and do not have much of an overhang, with pitches of around 30º-35º.

There are chimney designs peculiar to authentic Lakeland farmhouses. They are conventional at ground level but once above the line of the roof, they become round, tapering turrets using small stones, which were hard to cut into precise square corners. End chimneys were corbelled out from the wall at high level because the lower part of the flues were made from lath and plaster rather than masonry, offering no support below. The flues were capped off with two slates, leaning into each other to protect against snow and rain.

In western Lakeland areas, dark grey/pink granite boulders were available for wall building, but in such irregular shapes that they were placed in alternating courses with long thin slates and small stones to reduce the amount of mortar needed.

Windows were squarer, with vertical sliding sash frames, or sometimes split horizontally with a top opening light hanging out over a fixed lower pane. The oldest surviving farms have a small covered veranda tucked under an extended main roof with an oak balustrade. No one is quite sure what these ‘spinning galleries’ were used for – possibly making or airing yarn.

Westwards toward the coast there is a sudden change in the geology from volcanic rocks to soft New Red Sandstone, and this is neatly mirrored in the dark red buildings, still with the green slate roofs characteristic of the Lakelands. Further north in the Cumbrian coalfields, the later 19th-century houses of workers and miners are mostly rendered and painted in bright, contrasting colours. Rendered and painted walls are particularly found towards the coast, where the building stone is of a lesser quality.

In contrast to the architectural quality of Cumbria and the Lake District, the buildings to the east of this region are more austere. The traditional houses of the northern Pennines are similar in character to their cousins in the south, albeit in a darker stone from the carboniferous and occasional volcanic rocks found in the area. Historically this was never an area of great wealth, so the cottages are mostly small and modest: low lying, low pitched and built from poor-quality building materials.

North of the Tyne there are few villages but many compact hamlets, clustered together in a defensive fashion as a direct result of their location in border country, subjected for centuries to raids and skirmishes between the Scots and English. The classic layout has at its centre a four-square farmhouse with cottages and outbuildings huddled around it, all made from brown stones and grey slates. Further to the north east around Bamburgh, pinky-grey limestone is the usual building material, with bright red pantile roofs.

The Pennine range extends over half of this region, flanked by a small lowland area of Lancashire plain.

Here, the stone farms and cottages are distinctive, partly because there is such a close link between the appearance of the buildings and the surrounding landscape. The southern end of the Pennine range is mainly Millstone Grit, which is hard, coarse and massive – it varies in colour from dark grey to hard pale buff, often blackened by industrial pollution.

This sketch shows a traditional Lancashire house with a rendered and painted finish

This sketch shows a traditional Lancashire house with a rendered and painted finish

In the late 17th and 18th centuries many West Yorkshire farmhouses and cottages were built with workrooms on the upper floor where ‘weaver’s windows’ were constructed to allow as much daylight in as possible. There were up to nine lights (panes) in a row, divided by gritstone or limestone mullions. Eventually this cottage industry declined, but the windows were still built as a feature long after the factories took over.

A technique of building up door jambs utilising one or two long and thin vertical stones (rather than using walling masonry) is unique to later Pennine-style buildings, and made possible due to the availability of stone in large slabs. Roofs were covered in sandstone and gritstone in huge heavy slates, which easily kept the water out, so pitches are low – usually 30° or less.

The Yorskhire Dales and central Derbyshire are formed from carboniferous limestone, which creates a different landscape to the grit. This pale grey stone can be seen in the form of cliffs, gorges and pavements. All houses built of limestone in rough courses of rubble have darker corner stones of grit.

In the Yorkshire Dales older farms have low pitched brown stone roofs. Walls have long stones that run through the wall, which bond the inner and outer leaves – these were often left projecting out to save cutting the stones. Older buildings have small windows with elaborately carved door lintels, using traditional varied patterns, incorporating the date and initials of the owner.

The North York Moors are an upland region with yellow and grey sandstones and bright red pantiled roofs. Farmhouses are typically two storey with a byre attached at one end, lower than main house, and barns were built separately.

The main feature of lowland Lancashire is the use of external render, made with grit, sand and lime, which was whitewashed or colour washed. Sometimes the window and door surrounds are painted black, grey or dark green in contrast to the white or yellow painted windows and doors. Rendered walls had either stone corners and window surrounds, or render painted to look like stone.

Comments are closed.