Post & Beam Explained

It’s back to the future for enthusiasts of timber-frame construction, as one of its oldest varieties – post and beam, a system dating back 4,000 years but particularly famous in 17th- and 18th-century New England – is making a comeback among self-builders. “There’s one real reason why self-builders want a postand- beam home,” suggests Tim Crump of TJ Crump Oakwrights, one of Britain’s largest post-and-beam designers and suppliers. “That’s because it looks so good. If you don’t want to see beams inside, go for mainstream timber-frame methods,” he insists.

What is it?

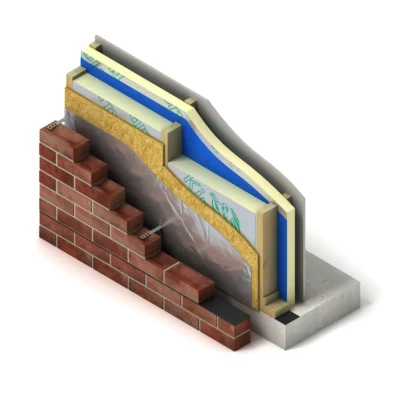

Post-and-beam construction uses large, widely-spaced wooden members to provide structural support and effectively creates a frame into which walls are then ‘placed’. With the beams carrying the load of the roof, it is not essential to have large numbers of interior walls, so it is an excellent construction method for open-plan homes. Different columns (the ‘posts’) and beams act as structural support for vertical loads, while sometimes diagonal posts are required for lateral loads. The posts and beams act as ‘carriers’ for any exterior cladding or finish, and for the interior walls if there are any. They also provide space for insulation.

The history

Post-and-beam construction, as we know it, began in the 1600s and traditionally uses timber throughout for beams, columns, girders and purlins for the structure, as well as for floors and roofing. Four centuries ago, hand-hewn timbers were joined together by hardwood pegs, or by joint geometry as one beam slotted on top of or alongside another. Conventionally, mortice-and-tenon joints turn the posts and beams into a solid structure. Traditional ‘mainstream’ timber-frame construction, by contrast, normally uses cheaper wooden wall panels that are placed into position, to create an exterior boundary of the property, and interior walls, too. These all collectively carry the load of the roof.

The down side

On the face of it, there are certain disadvantages to post and beam over mainstream timber-frame. Firstly, it costs more – around 20 per cent to 25 per cent according to experts. This is mainly down to the extra labour that is needed for post-and-beam construction, because the foundation costs are common to both.

Secondly, it is more time-consuming to construct; typically it takes four to five working days to build the frame of a post-and-beam house, whereas the overall frame of a panelled ‘mainstream’ home of comparable size, could be up within a day or two. Obviously, this is weather and workforce permitting.

The overall build of a 185m² (2,000ft²) four-bedroom home, including any outer skin, putting on a roof and making it watertight, may take up to four working weeks – which is possibly a third longer than a panelled home of the same size. For that reason some timber-frame home suppliers have relegated post-and-beam construction to outbuildings where large open interiors – the method’s unique selling point – are essential. “We only use post and beam if a buyer specifically requests it, and even then just for small units like garages,” says a spokesperson for Cedar Self- Build Homes.

The bright side

If time and budget are not paramount, the spacious style and sustainability of post-and-beam homes may provide compelling advantages. The most popular raw materials used for post-and-beam construction include pine, oak and Douglas fir.“Oak is especially useful in terms of sustainability,” explains Tim Crump. “It stands up to fire for longer than steel, it looks better with age, and is expected to last for around 300 years or more.”

Some types of wood – mainly pine, which is commonly imported from the US – have to be heat-treated to conform to EU regulations concerning beetle infestation. In addition, both pine and fi r require a fire-retarding spraying once the frame is in place. For cosmetic reasons, some self-builders insist on a ‘fingerprint resistent’ varnish being applied to the wood, too. The price will vary but these treatments could cost up to £800 for a mainstream four-bedroom property, with an area of around 2,000ft² (185m²).

Inner beauty

While beams are always on display inside post-and-beam houses, it is common for them to be fully concealed on the outside by an exterior skin, which is rendered or covered with weatherboard or sometimes cedar ‘featherboard’, in order to maximise the New England appearance. As a result, it is commonly the case that a post-and-beam property cannot always be recognised from its exterior. But, it is the space and dramatic interior design that allows post and beam to come into its own.

Some specialist suppliers like Timberpeg – which makes customised builds as well as having 50 off-the-shelf designs available – has beams that allow unsupported spans of up to 9.7m (32ft), permitting large open rooms, and the system encourages large, vaulted ceilings and so-called ‘cathedral spaces’. “The construction method also lends itself to late changes, so if you want to modify room boundaries or knock through two rooms to make one while you’re building, it’s a pretty easy thing to do,” says Timberpeg’s Jonathan Cobb.

Single-, double- and triple-glazing are all entirely feasible but the most striking element of post and beam is that it allows a whole gable end to be used for a dramatic doubleheight window, without losing any of the structural integrity of the property, as beams at the top of the glazing can be load bearing to support the roof. Common self-build components like underfloor heating, central vacuum systems and wiring to facilitate remote control heating and home entertainment systems are also all straightforward in a post-and-beam property.

But one potential drawback is that the main post-and-beam designers and suppliers are not as advanced as some developers in advocating eco-friendly insulation. Partly, this is because insulation tends to be ‘within’ the spaces between posts and beams so some manufacturers have ‘units’ made to slot into the pre-determined spaces. Foam board insulation, such as the type provided by Celotex and Kingspan, is straightforward and used by most suppliers on the grounds that there is substantial demand and therefore economies of scale are available.

Some suppliers are experimenting with so-called ‘breathing walls’ using a mix of hemp and cotton, or blown newspaper, or sheep’s wool, which would be of equal, or potentially, higher insulating quality and certainly more eco-friendly. But this is still an unusual request for post-and-beam suppliers, so be sure to check if this is an important element of your self-build project.

The future of post and beam

Although post and beam is one of the oldest construction methods, there are innovative approaches being considered in the US, and they are likely to spread over here, too. So-called ‘modular post and beam’ involves subsections of a post-and-beam house being factory-made and then winched and bolted into place – so instead of a house consisting of, perhaps, 100 beams, it is made up of eight pre-built ‘beam units’.

In addition, there is considerable use of composite woods such as glulam, Parallel Strand Lumber (PSL) and Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL). These are artificially compressed woods that have the advantage of being manufactured in lengths of up to 24m (80ft) or even more. A major benefit of glulam in particular is that it can be made into curved and shaped beams – heresy to the post-and-beam purist, perhaps, but increasingly in demand across the Atlantic. PSL and LVL are very new; although manufactured in straight sections, multiple units of these compilation timbers can be laminated on site to produce longer or thicker beams. Therefore, transportation costs for larger beams can be minimised.

Meanwhile, we are not without home-grown innovation. “Many British clients now want more contemporary interiors to complement traditional wood,” notes Tim Crump. “So we’re getting a lot of requests for substantial volumes of glazing – especially if there are good views – plus traditional galleries and beams, white walls and highly modern steel kitchens. The appearance can be quite dramatic.”

Post and beam, it seems, is renewing itself for the 21st century. It’s expected to last a long time yet – and look very beautiful with it.

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.