Barn Conversions: Spot a Renovation Opportunity

By Victorian times, farms had become larger and more mechanised, with improved animal husbandry methods requiring many different building types, each for a specific use. The Victorians idealised the rural lifestyle, constructing many farmhouses that were reproductions of genuine vernacular structures.

There is a wide variety of farm building types, each with their own history of development, plus a host of regional variations. If you know what to look for they can all be identified, since the designs reflect their uses in a very direct and practical way.

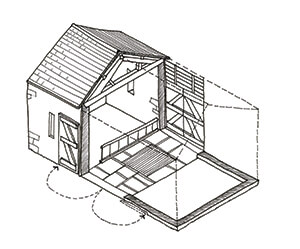

Threshing barn

Before the grain could be stored, it had to be separated from the plant and collected. To do this, the stalks had to be beaten and the mix of grain and its unwanted casing (the chaff) thrown up into a light wind. The wind would blow away the chaff, leaving behind the grain, and threshing barns were designed to allow this process of ‘winnowing’ to be carried out in sheltered, more controlled conditions.

All threshing barns have three or five bays, with a large double-height opening on each side of the central bay where the winnowing took place. The large high doors spanning them were opened and closed to regulate the speed of the wind and also allowed a cart to be driven into the barn for unloading.

The rest of the external walls were studded with a regular series of small vent holes at ground and first floor level to keep the straw and grain as dry as possible. The size and shape of the vent holes were determined by the local weather conditions, such as the strength and direction of the prevailing wind.

Another distinctive feature of a threshing barn is the grooves at the bottom and either side of the large openings. These allowed timber boards to be slotted into position during winnowing, to prevent the grain spilling out of the barn.

See Simon Forrester and Andrew Craven’s converted threshing barn.

Farm stable

From the end of the 18th century until the second world war, horses were the most precious livestock to be found on any farm (before that, the heavy work was done by oxen, and after, the tractor became dominant).

Stables have to be well-lit and well ventilated, with enough space around each animal for it to be groomed. Unlike cattle, horses were given individual stalls, and stables had plenty of windows, which were sometimes glazed.

They were built with a row of regularly spaced doors, each with a top that opened separately, known as a heck or half door. The interiors were rendered in breathable lime plaster to absorb the sweat from the resting horses and allow it to evaporate and be ventilated to the outside air.

Aisled barn

Most are in England’s south east but a few can be found further north in areas such as the Pennines. They were created for the storage and processing of sheaves, although many have since been adapted for other uses, such as livestock or farmhouses. They were also used for threshing and winnowing on a much larger, semi-industrial scale.

Aisled barns’ high roofs sweep down to ground level and porches were built on either side to create the required large openings. Inside, they are strikingly similar to a church, with aisles positioned on either side of a central space, typically divided into three or five bays. The aisles were a way of increasing the floor area without using impractically heavy timber beams.

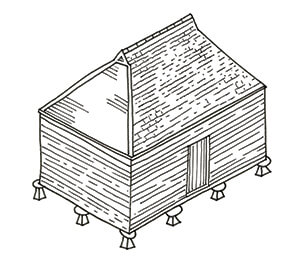

Granary

Windmill

These icons of the rural landscape first appeared in the 12th century and come in three types. Post mills are constructed around a massive central column of oak, which allowed the upper timber section of the building holding the sails to be turned around to face the wind. Its brick or stone base, known as a roundhouse, was used for storage.

Tower mills are of a more substantial construction and made entirely of sloping brick or stone, which allowed the sails to be raised higher to reach stronger winds. The sails were connected to a cap, which could also be rotated to face the wind. A smock mill is similar to a tower mill but built entirely from timber.

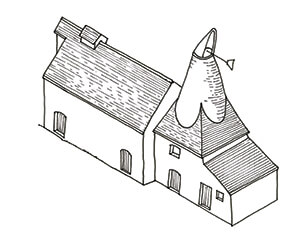

Oast house

In the 19th century it was believed that the rounded form made drying more efficient; it was a difficult shape to construct, however, so by the beginning of the next century the shape became square. The proportions of the hop kiln were dictated by the use of timber fuel, but once coal became widely used, separate chimneys were built to prevent the fumes spoiling the taste of the hops.\

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.