An Expert Explains How to Understand Your Heat Pump’s Performance & Efficiency

Heat pumps are often sold based on impressive-sounding CoP (Coefficient of Performance) figures. But what’s behind these numbers, how reliable are they and do they reflect what a heat pump system will actually achieve in real-world conditions?

To make sense of the data – and understand whether your install will save money compared to a boiler – you need to ditch the sales pitch. When investigating true heat pump performance, a good place to start is the difference between the three main measures: CoP, SCoP and SPF. Here, I’m looking at what CoP and what this means for your heat pump’s overall efficiency.

What is a heat pump’s coefficient of performance (CoP) & how is this calculated?

A heat pump’s coefficient of performance (CoP) is a measure of efficiency conducted in a laboratory environment. Put simply, a CoP represents the heat energy you get out of the appliance, divided by the amount of electricity required to run the pump:

CoP = Heat output divided by electricity Input |

So, if you could produce three units (usually kilowatt-hours, kWh) of energy out of a heat pump for every unit of electricity input, then the CoP would be three (3/1 = 3). People selling heat pumps often quote the CoP figure – but the fact it’s achieved in laboratory conditions means it isn’t generally replicable.

Remember, the CoP is only a snapshot over a short period of time in standardised conditions. This is typically meant to represent a 7°C external air temperature and 35°C water output (which essentially relates to an optimal system in a well-insulated home with underfloor heating, so CoP in a retrofit is likely to be lower). Depending on the heat pump type, there may also be values for 55°C and 65°C output (which is the same range a boiler would deliver).

Real-world performance varies by season, as well as day-to-day. An air source heat pump (ASHP) will be more efficient in summer than in winter, because the temperature of the heat source (the air) is higher in the warmer months. It will still do its job in winter, of course, but there will be frosty mornings and milder days that impact efficiency.

Ultimately, the CoP used in sales brochures has quite a lot in common with the factory-measured mpg (miles per gallon) figures we’re often quoted for cars. It can be useful for comparing different heat pumps, but doesn’t represent the actual performance you can expect over a 12-month period – and this is what we really need to know.

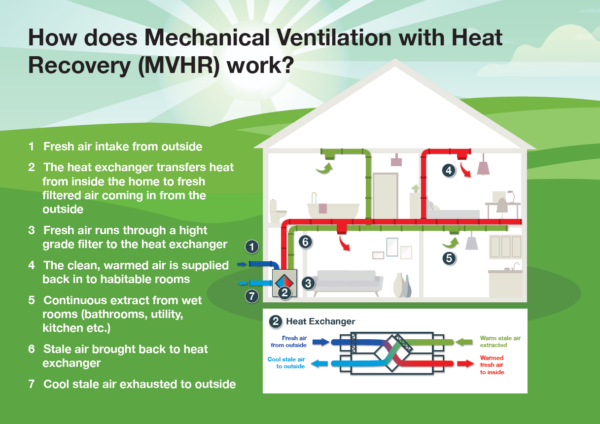

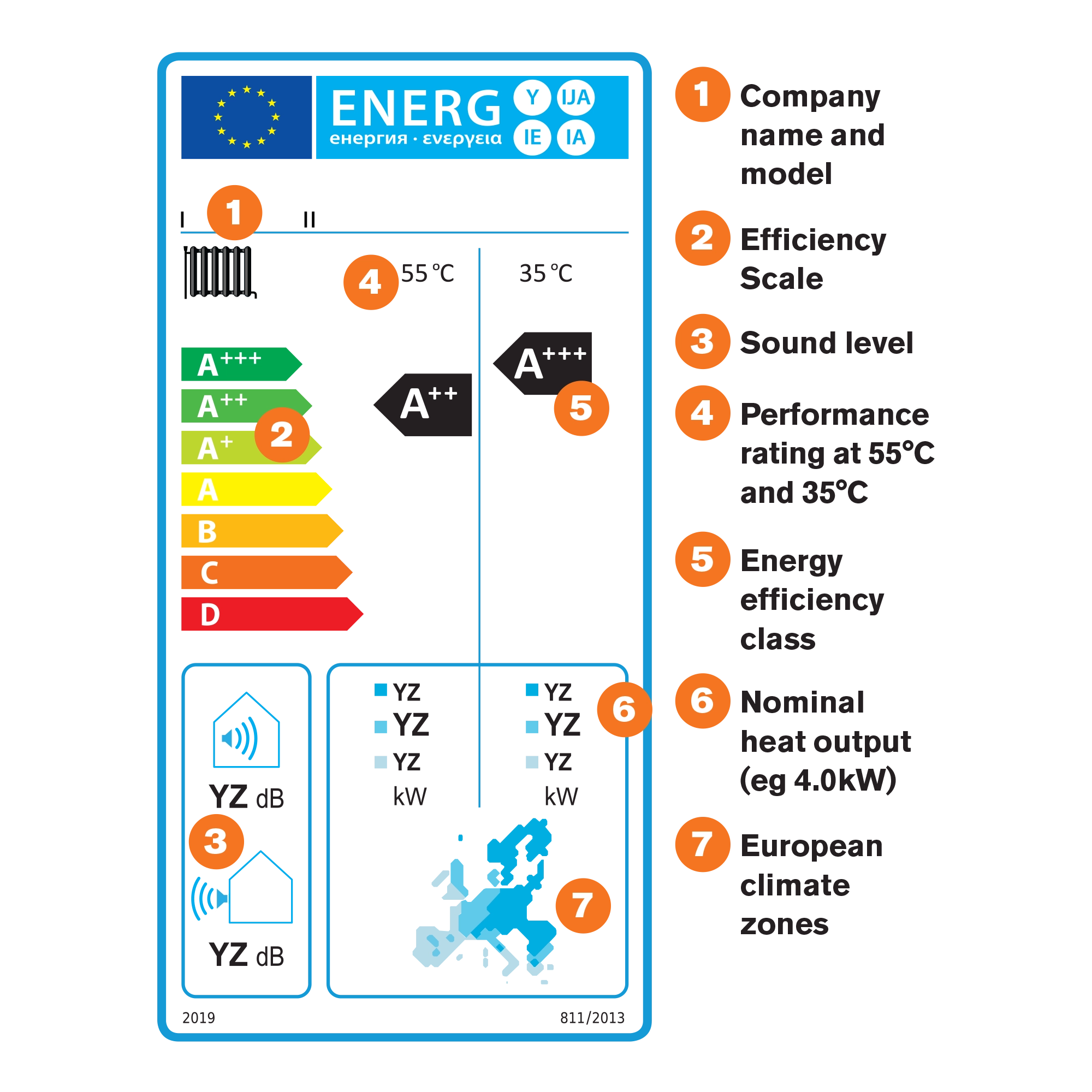

This is what a heat pump ErP label looks like

What is a heat pump’s seasonal coefficient of performance (SCoP)?

As the name suggests, Seasonal Coefficient of Performance (SCoP) measures annual performance based on varying weather conditions throughout the heating season. It is, therefore, a step closer to reality – but is still calculated rather than measured. The formula that produces a SCoP rating uses the instantaneous CoP as a starting point, then follows an international standard to derive an annual figure.

This is based on a weighted average of tested CoPs at various outdoor temperatures (intended to reflect different times of year). British Standard BS EN 14825:2022 provides a detailed methodology for calculating a heat pump’s SCoP, including the required climate data, test procedures and temperature profiles for each climate zone.

Freddie and Katie Pack specified a Vaillant air source heat pump via Solaris Energy for their countryside self build, which allows the couple to run a low energy property with minimal long-term costs. Photo: Richard Gadsby

SCoP is used by manufacturers to describe product performance. It’s also used to calculate ErP (Energy Related Products) ratings and as part of the design standards for the Microgeneration Certification Scheme. So, it’s an important metric, used in official government schemes.

There remains, however, a significant gap between the figures it generates and real-world performance. Indeed, a recent government study based on Ofgem data showed that SCoP overestimated performance by an average of 30%. So, what’s the alternative?

How can you calculate a heat pump’s seasonal performance factor (SPF)?

The Seasonal Performance Factor (SPF) is a true measure of the performance of a heat pump system over a 12-month period, rather than a modelled estimate like CoP or SCoP. It’s determined as follows:

SPF = Total measured annual electricity input divided by total measured annual electricity input |

Two recent major government studies (using data from actual installs) have revealed that the median SPF of air source heat pumps is 2.7 to 2.8. So, over the course of a year and depending on your setup, on average you could expect to achieve 2.7-2.8kWh of heat output for every 1kWh of electricity input. That’s far lower than manufacturers’ typical SCoP figures.

Here’s how measured SPF compares with quoted SCoP, according to an analysis of Ofgem data for installations monitored between 2017 and 2022:

| Heat pump type | Number of installs | Median SPF (measured) | Median SCOP |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASHP | 1,431 | 2.69 | 3.59 |

| GSHP | 286 | 3.26 | 3.93 |

Assuming good design and installation, ASHPs in highly efficient new buildings – homes that have low temperature distribution (such as underfloor heating), low overall heat demand and a well-optimised control system – will achieve better results than this. But bear in mind that an equal number of installs in these studies achieved worse than the median.

Ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) achieved higher SPFs – an average of nearly 3.3. This is to be expected because the temperature of the heat source (the ground) should be higher in winter than the air.

Rated at an output of 5.8kW, UK manufacturer Kensa’s Shoebox NX ground source heat pump offers a compact, high-performance option for space heating and hot water in flats and smaller homes up to five bedrooms

Unfortunately, your heat pump supplier won’t be able to quote you an SPF because actual performance depends on many factors – including local weather conditions, building heat loss, system design, installation quality, user behaviour and more. At the moment, the best you can do is look at the government trials (In Situ Heat Pump Performance and the Electrification of Heat Demonstration Project) and try to understand whether a heat pump is likely to deliver better results than the averages quoted, given your property type and lifestyle.

Interestingly, the MCS has recently dropped SCoP in favour of standardised SPF figures in its guidelines for pre-sale performance estimation. The newly revised approach considers both the specific heat loss of the property and type of system, cross-referencing this with a lookup table of SPFs at different flow temperatures to give an indication of expected performance in-use.

find renewable energy suppliers

How does a heat pump’s performance impact your energy bills?

Now that we understand realistic efficiency, let’s see how this translates into running costs. Electricity is expensive in the UK. It’s costly to use it for producing direct heat, but we do this every time we boil a kettle, use the immersion heater or switch on an electric space heater. Electricity is currently about four times the price of gas per kWh, but (in the absence of a heat pump) they produce almost the same amount of heat.

For homeowners currently using direct electric heating (such as electric radiators, storage heaters or fan heaters), you’ll instantly start saving money and CO2 emissions by installing a heat pump – whatever its quoted COP performance – because you’ll inevitably be improving system efficiency beyond 100%.

If you’re thinking of upgrading from a gas boiler to a heat pump, however, then – because electricity is so much more expensive – you would typically need to achieve an SPF of around 3.6 in order to match the existing system’s running costs. In the right property and with good system design and installation, that is possible. But the evidence suggests that most ASHP installs don’t currently achieve this level of performance, although more GSHPs may get there.

Let’s crunch the running costs of a heat pump based on currently available data:

For this, we’ll assume an SPF of 2.8 (the better ASHP median value from the two government reports); an electricity price 3.8 times the price of gas per kWh (current Ofgem price caps); and gas boiler efficiency of 90% (typical of modern appliances). Here’s what we get:

| Input per 1 kWh of heat output | Cost per 1 kWh of heat output | |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Boiler | 1/0.9=1.1kWh | 1.1x6.99=7.77p |

| ASHP | 1/2.8=0.3571kWh | 0.3572x27.03=9.65p |

In other words, at these performance levels, delivering the same amount of heat via a heat pump would cost 24% more than using a modern gas boiler. Of course, running cost is not the only important issue when it comes to heat pump efficiency. The fact the UK’s electricity grid has significantly decarbonised means that even a heat pump operating at a SCoP of 2.8 should save on CO2 emissions versus a gas boiler.

Peak grid demand in midwinter is a major issue, however, and the more efficiently we can use our electricity, the lower the environmental and financial cost will be as we upgrade the National Grid to adapt to the electrification of heating. The government is aware of this and, among other measures, is currently consulting on proposals to incrementally increase the minimum efficiency standards for heat pumps.

How does your your specific house & heat pump’s installation affect its real-world performance?

A heat pump’s actual efficiency in use depends on a range of key factors, including your property’s location, nature of the building fabric, distribution system, occupancy patterns and proportion of hot water demand versus space heating.

Location influences the temperature of the heat source. Ground and air temperatures are higher the further south you go in the UK, which can boost efficiency. Local conditions such as exposure also play a part.

Building fabric determines how quickly heat is lost. Heat pumps are best at delivering heat low and slow, unlike boilers which run hot and hard. Well insulated buildings retain warmth better and suit this steady approach to maintaining indoor temperatures.

Distribution is critical. The larger the emitters, the lower the distribution temperature can be. Having a smaller gap between the source and delivery temperatures means the heat pump has less work to do. Underfloor heating is ideal but not always feasible to install in existing houses; oversized radiators are an alternative.

Patterns of occupation vary widely. If you’re going to be in the house most of the time, you can run constant low-level heating, which will support optimal heat pump performance. If you’re out for much of the day and tend to heat your home in bursts, the heat pump will have to work harder for shorter periods – making it less efficient.

Domestic hot water (for washing etc) represents an increasing proportion of our energy use. A heat pump has to work harder to deliver hot water at around 55°C than to supply space heating at the ideal 35°C.

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later