Water Source Heat Pumps: Is It Right for Your Self Build?

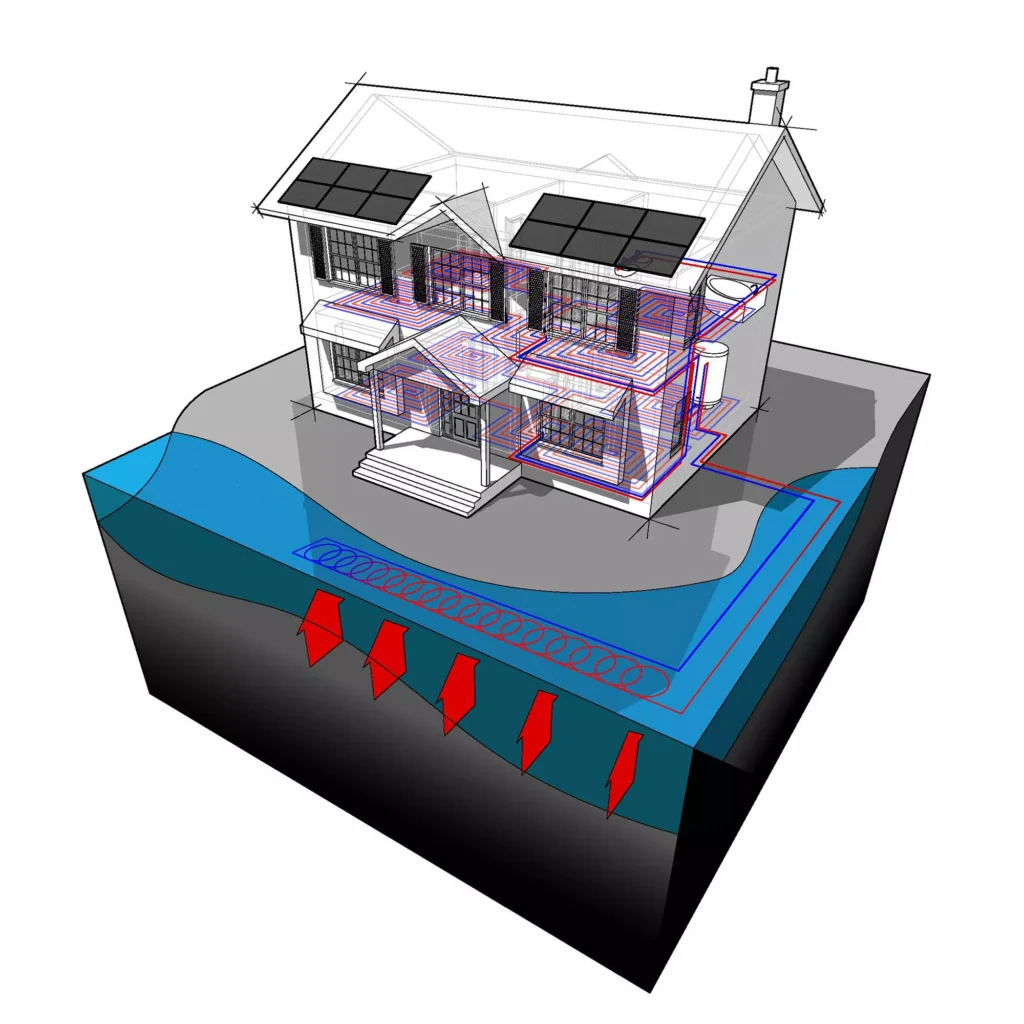

Heat pumps take heat from low-grade sources and compress it for use in space heating and hot water systems. The most common sources of the warmth they require to work effectively are the air and the ground, but heat can also be extracted from water – hence, water source heat pumps (WSHPs).

The greatest attraction of water source heat pumps is that the temperature of the heat source is likely to be better than either the ground or the air during peak space heating season. The efficiency of air source heat pumps (ASHPs) drops rapidly during the winter, when the air temperature is at its lowest – particularly during periods where defrost mode is required.

Similarly, after a ground source heat pump (GSHP) has been operating for some time, the temperature of the ground surrounding the collector loop will have fallen slightly – so, it won’t be operating at quite the same efficiency as at the start of the heating season. Water source heat pumps can draw their heat from rivers, underground aquifers, lakes or even in the sea.

Of course, the water temperature does drop during winter, but not as much as the air temperature. As water is a fluid, even in bodies of still water such as large ponds and lakes, the rate of heat recharge (to the area from which heat is collected) is likely to be more efficient than with a ground source heat pump, which draws its heat from static material with slower heat flows.

Looking for sustainable products for your eco project? Browse Build It’s product directory full of top suggestions

Can I Have a Water Source Heat Pump?

The reason water source heat pumps are rare is that very few buildings have a convenient body of water nearby. For homeowners, the choice narrows down to river (or stream), underground aquifer or a pond/lake, as the engineering involved with marine sources is likely to be prohibitive for small water source heating schemes.

As with all heat pumps, WSHPs work best with low temperature distribution systems such as underfloor heating. They also work better in homes that have high levels of insulation and good airtightness, where space heating demand is already low and the building cools down more slowly. While the same could be said for gas boilers, heat pumps don’t have the capacity to produce quite as high a temperature, hence warm-up times aren’t as fast.

Good energy performance is almost standard in new homes these days. So, if you’re self building and have access to a suitable body of water, then you can almost certainly install an effective WSHP system.

It’s very difficult to retrofit existing houses to the same standard – so you can’t expect the same performance from a heat pump that you would get in a new build. That said, it could still be the right choice for an existing home depending on what fuel type you’re replacing and what you’re planning to do in terms of insulation, emitters etc.

Learn More: Choosing a Heating System for Your Self Build : Radiators or Underfloor Heating?

A water source heat pump collects warmth from a body of water, before compressing it to deliver efficient, low-carbon space heating and hot water

Types of Water Source Heat Pump

Water source heat pumps can be either closed loop or open loop. They can range in size from small domestic at a few kilowatts (kW) right up to large district heating schemes with outputs of several megawatts (MW).

In a closed loop system, a heat transfer fluid circulates between the heat pump and the collector. Closed loops are common for small-scale applications, such as in streams and modest rivers where abstraction (removal of water) could cause issues. These systems are designed to be robust and leak-free.

To further protect the environment against any residual risk, low-toxicity glycol-water mixes are used. You may also want to check out the transfer fluid’s global warming potential (GWP) and ozone depletion potential (ODP).

Open loop designs take water out of a lake or aquifer, extract (some) heat and then return the water to its source (or nearby). A big pond or lake can be appropriate for a WSHP, depending on how deep it is, the water temperature and its rate of heat replenishment (being fed by a ground water spring would be beneficial, for instance). These factors will determine the appropriate collector size for the body of water – it mustn’t be so large that it might lower the temperature in the lake.

Looking for ways to save on energy around the home? Read our guide on the 12 Ways to Save on Home Energy Bills

What Makes a WSHP Run Efficiently?

The most efficient heat pump I’ve ever encountered used a closed loop collector located in a small stream – a chalk stream to be precise. Firstly, this meant that there was a steady flow of water all year round.

In this case, there’s only a short distance to the buildings it was heating, too – so losses from the pipework are low. The stream is also shallow, so the energy needed to pump the water round the collector loop is minimised. What’s more, as the point of collection within the stream is not too far from the source of the stream itself, the temperature of the water never falls too close to zero.

This water source heat pump features collector plates installed in a chalk stream, delivering excellent performance

There is a lower limit to the source temperatures at which WSHPs can operate. Extracting heat from a liquid at near 0°C means that, in an open loop system, the water leaving the heat pump may run the risk of freezing. Even the sea can freeze if the temperature gets low enough.

So, open loop systems can only operate down to about 5°C (3°C for closed loops), and in lakes a WSHP will be more effective if there is good circulation/recharge. Where there is a risk that temperatures can drop below this level, a bivalent system is needed – ie some form of back-up boiler.

By contrast, an underground aquifer is likely to have a high consistent temperature all year round. In the right circumstances, this can deliver cheaper installation, better performance and lower running costs. In areas with underlying chalk, for example, the aquifer is likely to be not too deep, so the cost of drilling would be reduced.

Aquifer heat pumps are in a sense similar to ground source heat pumps. However, this type of WSHP tends to be more efficient as the source temperature remains more consistent than with GSHP boreholes. Depending on ground conditions, drilling one shallow borehole for an aquifer could also be preferable (and possibly cheaper) compared to installing a large horizontal GSHP collector.

Planning your self build project but don’t know how much it’ll cost you? Read our guide to How Much Does it Cost to Self Build a House in 2023?

Do I Need Permission for a WSHP?

Every situation is different, so always check with your local authority and Environment Agency (EA) as to whether any consents are required. In general, however, planning permission is only likely to be needed if the installation changes the appearance of the property significantly. By its very nature, a WSHP is a much less visually intrusive technology than other forms of renewable energy.

In this Hex Energy project, three WSHP collector mats were fitted at a depth of 5m in a 0.75-acre lake within a former quarry. The heat load was 12kW

In terms of environmental permits, the EA is usually principally concerned about installations that raise the temperature of a body of water. This is due to the effect of high water temperatures on aquatic life.

A WSHP reduces the temperature of the body of water from which it draws heat, so may not require consent. That said, open loop systems are more likely to need EA permissions, as they extract and then (usually) return the water to the same place (albeit at a lower temperature). The larger the pump, the more likely the EA will get involved.

Learn More: Planning Applications: What Do Council Planners Want?

Costs & Subsidies of a Water Source Heat Pump

WSHP installations are still relatively rare in the UK, and each project must be bespoke priced depending on the nature of the water source, the building’s insulation levels, emitter type etc. That said, they can be an attractive alternative to ground source in the right circumstances.

Furthermore, under the Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS), domestic WSHP installations in existing houses and owner-occupied self builds are eligible for the same £6,000 subsidy as their ground source cousins.

The BUS is only available in England and Wales, and there are certain criteria to be met. For instance, you will need a current Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) and any recommendations on that EPC for loft or cavity wall insulation must first be addressed. Your installer must also be accredited under the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS).

Looking for advice for your sustainable self build project? Read more from our eco expert Nigel Griffiths

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later