Timber building & innovation

The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘innovation’ as ‘making changes in something already existing, by introducing new methods, ideas or products’. In the housebuilding industry, timber fits this description perfectly – a traditional building material re-emerging as a truly modern product that can be adapted to create sustainable, attractive and affordable modern buildings. So, what exactly is new? And how can you use the latest technology to help you build faster, cheaper and greener?

Composites

Timber itself is a wonder material, a natural composite flexible enough to be used for a huge range of building projects, from structural frames to window cases. Once converted into particles, strands or laminates and combined with other materials (such as glue) into a man-made composite, you get a product with all the benefits of natural wood but even stronger, more malleable, versatile and durable.

Glulam

Glued laminated timber, or glulam, is usually made from softwood, such as European whitewood, and comprises layers of planed timber glued together under high pressure. The resultant product is exceptionally strong – comparable to steel – making it ideal for load-bearing structures. It also looks great, with all the beauty of natural wood, but can span much further and be curved and shaped easily – perfect for intricate roof structures and exposed beams. Glulam is available from most timber merchants and comes in standard widths from 90mm to 240mm, with special widths of 265mm and 290mm available. Lengths of up to 2,050mm are standard, with a maximum of 31,000mm available to special order.

LVL

Manufactured from rotary peeled veneers glued together to form continuous panels, laminated veneer lumber (LVL) has excellent bending resistance, tension and compression properties, and a huge load-bearing capacity. As it rarely twists, warps or splits, LVL is great for the long spans required for roof and floor joists, as well as framework studs where extra strength is needed. Panels 1.8m wide can be cut to beam sizes with widths from 20mm to 600mm and thicknesses from 27mm to 75mm, to a maximum length of 26m. Prices vary depending on the brand of LVL you go for, but a structural beam (39mm thick x 220mm wide) from a brand such as FinnForest Kerto costs around £5.90 per metre.

Panels

A large variety of timber panels and panel products can be created for use in timber-built homes. They usually consist of small fragments of wood bonded together to create a sturdy board. Plywood Plywood is probably the most common type of timber board. Sheets of timber are glued together, with the grain of each layer at a 90° angle to the layer below. It is a highly versatile material that can be used for anything from wall and floor sheathing to interiors and fuselages. Depending on the type of wood and glue used, plywood can be weather resistant. It can also be used in some structural applications, but as its quality varies ensure that the correct grade is specified – British Standard 5268-2:2002.

OSB

Oriented strand board (OSB) uses logs not large enough to make plywood. The board is made from precisely cut strands oriented in predetermined directions and bound with synthetic resin. It is generally used for interior flooring, SIPs, wall sheathing and furniture (direct contact with water should be avoided). As well as being versatile, it’s ultra cheap, costing around a third of the price of plywood.

I-joists

Engineered timber beams or I-joists (they have the profile of a capital ‘I’ on the g end side) are used in place of traditional joists. Made by joining LVL flanges to a plywood or OSB web, and similar in design to a steel beam, I-joists are lighter than and span further than timber joists. Best for floor joists and roof rafters, I-joists eliminate the typical problems associated with solid lumber joists – they don’t bow, crown, twist, cup, check or split. They are so structurally sound, they can help eliminate squeaky floors and will barely shrink. The majority of the structural work is done by the top and bottom beams, so the web can have relatively large holes cut into it without weakening the joists in any way. In other words, you can run fairly large services through the depth of the floor without any problems.

Treated woods

Heat-treated wood, known as Thermowood, is softwood specially treated at up to 200°C, permanently changing its chemical structure to reduce its moisture content, expel resin and break down some of the natural sugars that can weaken the timber. The process makes the timber more durable and stable – reducing any shrinking and swelling by up to a massive 50 per cent – and imbuing it with many of the characteristics of a hardwood. Thermowood is particularly suitable for exterior cladding, decking, windows, doors and any products affected by harsh climatic conditions. It has a high resistance to fungal attack and decay due to fewer resins in the surface undermining the surface treatment.

Other treated wood products include Accoya, which uses a patented process that increases the amount of acetyl molecules present in softwoods. Acetylation protects wood from rot by making it inedible to most micro-organisms and insects, without making it toxic. It also greatly reduces the tendency to swell and shrink, so the wood is less prone to cracking; this ensures that when painted Accoya needs little maintenance, making it ideal for window frames, doors and cladding. The timber is guaranteed for 50 years against rot and has a 60-year life expectancy review from the BRE – which means it is basically risk-free.

House systems

Timber-frame construction is the darling of the self-build world, coming in many guises and lending itself well to modern design developments. Recent innovation has not been confined to timber products – construction techniques have also been developing rapidly. As almost all timber-frame systems have some factory-produced elements, the improved techniques have reduced defects and improved quality. The use of prefabricated panels significantly lessens the amount of time required on site, enabling completion of the weatherproof shell within a few days.

The majority of timber-frame systems will use one of the following:

Open panels:

This is the most popular panel method and has been used extensively with timber-frame houses for quite some time. Essentially, the factory-built panels consist of softwood studs to which is attached plywood or OSB bracing. Once on site, the panels are fixed to the timber frame, according to the manufacturer’s specifications; panels are left unboarded on the internal side (hence the name ‘open’) until the structure is weathertight. At this point services and insulation can be fitted and the panels closed with plasterboard or similar.

Closed panels:

Unlike the open-panel systems, closed panels are prefabricated off site in their entirety, and include insulation, vapour control layer, window and door linings, and services. This method is favoured by German and Scandinavian housebuilders, in such systems as Huf Haus. The panels are very heavy and machinery is needed to lift the panels into place on site, but assembly is very quick, and the building can be made airtight in no time at all; after which you literally just need to choose the finishings and cladding. Once manufactured, the wall panels cannot be drilled or cut, as all the service points have already been catered for, so a great deal of forward planning is needed.

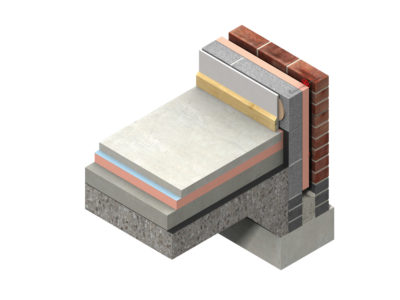

Structurally insulated panels (SIPs):

SIPs consist of two layers of board, usually OSB, that sandwich together an insulating product such as polyurethane, that is then precision-cut in a factory, creating an extremely airtight building envelope. The panels – 10 times stronger than conventional timber-frame constructions – can make up the internal and external walls of a house. They can also be used to replace rafters, creating a clear roofspace free from supporting joists, which also means a larger, open floor area.

Other innovations

To make modern building methods cost-effective and affordable, they need to be mass-produced, so the majority of developments in timber construction are geared towards volume housebuilders and commercial developers. This is especially the case with innovations such as whole-room prefabricated pods – the bathrooms and kitchens that are completely built off site, ready to be just dropped in place, fittings included.

However, there are one or two exceptions:

The Zone range:

Launched in April 2009, Potton’s factory-produced Zone range is a modular system of contemporary timber-frame garden studios, in five basic designs for one to four people. Construction is rapid. It’s entirely possible for a basic, one-person, 3m2 pod to be delivered in the morning and be in use in the afternoon; a four-person office/studio will take two days. The small timber frame and components – 140mm stud walls insulated with Kingspan, fully fitted with services and wiring, and ready-finished inside and out – are designed to be erected on cramped sites. Prices start from around £5,000.

The Facit system:

For real innovation and bespoke design, the Facit system is new on the scene. Suitable for self-builds and larger projects, it is based on a series of prefabricated cassettes that are easily joined together to create the fabric of a house – cheaply, easily and in an environmentally friendly way. You design your dream home, down to the last screw hole, on a computer, alongside a member of the Facit team. The layout is spilt into a series of different parts, which are then cut out using a computer controlled cutter. Unlike other prefabricated techniques, the cutting actually takes place on your plot in a compact mobile production facility. Rapid assembly on site is helped by the fact that every component of the building is automatically numbered to make construction easier.

The Facit team believes anyone can put together this house system, even with limited construction knowledge – they describe it as building with Lego blocks, and you can’t get much easier than that. You don’t even need a crane as the blocks are so lightweight. Even better, only wood from sustainable sources is used and the components, including I-joists, are thoroughly modern. The system costs around £250 per square metre of floor area, but the total construction cost will depend on location, fixtures and finishes. You could save around 20 per cent of the cost of a traditional architect-designed home.

Main image: The innovative Facit system is prefabricated in an on-site factory

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Comments are closed.