Choosing Insulation for a Timber Frame Home

When it comes to the energy performance of timber frame and masonry building systems, there are some key design differences between the two.

Unless you are thinking about solid wall construction, the fundamental distinction between masonry and timber frame is the non-negotiable need to preserve a cavity between the inner timber structural panel and outer cladding skins, which must be kept free for ventilation purposes.

With brick-and-block, the gap can be usefully insulated to boost a masonry structure’s performance while attempting to prevent the total wall thickness from becoming too great.

That’s not the case with timber frame, where the structural panel does everything: taking load by supporting floors and roofs, providing rigidity to stop the structure from a lateral twist and containing the insulation required for acoustic and thermal performance.

| Considering different build systems?

Once you have a plot, the next key decision is which build route is best for your project. Timber frame, ICF, brick, masonry, hemp, SIPs, CLT or steel frame? All have their benefits and downsides. At Build It Live you can speak to experts representing each of the main build systems, so you can choose the best option for you. Watch live presentations and get your questions answered on topics such as:

Build It Live takes place three times a year in Kent, Oxfordshire and Exeter. The next show will be on 8th and 9th June 2024, in Bicester, Oxfordshire. Claim a pair of free tickets today and start planning your visit. |

The physical properties of a timber panel are important. The selection and mix of the individual components should be treated much like a formula or recipe – some vanilla, others more exotic, with a staggering range of prices from a big supplier pool all competing for your business.

Timber panel design components

An open-cell timber panel is made to a given height and usually to a standardised width, with special sizes to suit building dimensions, plus window and door openings. The panel is made from structural timber studs/rails, which form a perimeter frame and include intermediate vertical studs at no more than 600mm centres.

The hollow frame is formed into a panel by fixing a layer of rigid board, typically to the outside. This sheath locks the frame together and stops the rectangular or square shapes from becoming rhomboid.

EXPERT VIEWInsulation Options for Timber Frame HomesDave Ashbolt from Materials Market takes a look at the key benefits of different timber frame insulation types: Rockwool & mineral wool

PIR (polyisocyanurate)

|

This rigid (racking) board is most commonly a sheet material like OSB (oriented strand board) but could equally be plywood, MDF, Fermacell (made from gypsum and paper), Panelvent (a wood-chip derivative, without using glue) or magnesium oxide board, among others. Where window openings are located, the panel will also include a timber lintel which will be supported by additional studs.

If the racking board is applied to the outside – as is most common in the UK – then this outer surface will usually be covered with a breather paper which will protect it from weather but allow the passage of moisture vapour.

Most panel manufacturers will apply this in the factory with nylon strips to show where vertical studs are located and with overlaps (temporarily folded back) that are included for sealing each panel to its neighbour.

Timber stud sizes are most commonly 38mm x 140mm sectional timber (treated softwood) which is one of two main industry standard sizes and referred to as CLS (Canadian Lumber Stock) as its origins are from North America.

The very fine wood of Northern Europe uses a different metric equivalent at 45mm x 145mm (TR24) or C24 stress graded timber, which may come out at 47mm x 147mm. For most timber frame users, the insulation options are all built on, into and around this panel chassis.

Popular insulated timber frame systems

Take a walk around any one of the exhibition halls at Build It Live and you’ll come across a vast range of panelised products, each designed to differentiate it from the competition and to help justify a variance in price.

Some add insulation in the factory, others take it one stage further and line the interior panel face with a vapour-control layer and possibly electrics and conduits. Some include a built-in service channel and others extoll the virtues of two separate stud walls with a clear insulated space between.

In picking some examples for a bit more focus, the following three generic types should cover most options:

Model 1

The first route is the conventional core panel with an additional layer of sheathing insulation in the cavity. This provides an easy opportunity for a service zone internally by adding a counter batten after the vapour control layer to give you whatever thickness of void you want for mechanical and electrical installations.

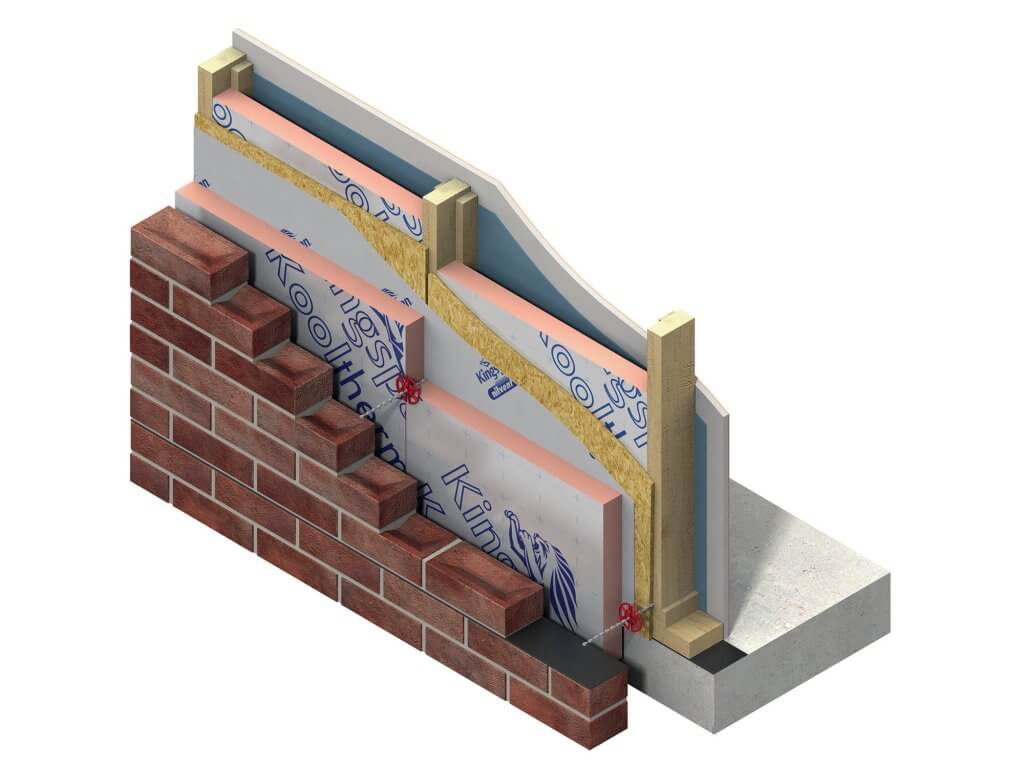

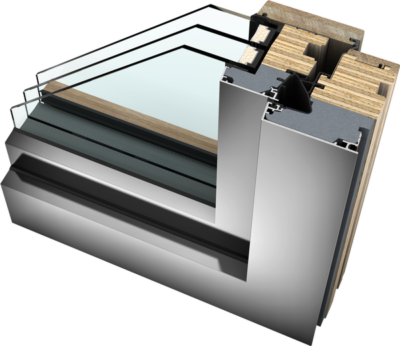

Using PIR (polyisocyanurate) rigid foam insulation as an example, impressive U-values can be achieved as calculated and published by one of the leading manufacturers (see Kingspan image, above right). Using a 140mm timber stud (selected for frame rigidity) with 60mm PIR insulation between the studs and 60mm PIR as an insulation wrap around the outside, you can attain a U-value of 0.16 W/m2K.

This could be improved to 0.15 with a rendered external block or reduced slightly to 0.17 with a lightweight cladding hung on the panel as opposed to brick. If you were to take the full 120mm insulation thickness and put it all as a wrap around the outside of the panel (with no insulation between the studs) the U-value could be improved to 0.14 for a build finished in rendered blockwork.

This confirms the effect of thickening the external insulation wrap rather than using the space between the studs, which eliminates the effects of cold bridging from the timber studs themselves. This technique is much more significant when it comes to steel frame, since a steel stud is much more conductive than timber.

However, the negative effect of doing this is an overall thickening of the external wall, which has the potential to reduce the amount of useable internal accommodation and potentially require an increase in foundation thickness.

This could be mitigated by using a more slender stud size, for example 89mm as opposed to 140mm, but the rigidity of your frame will then be reduced. So, like most design decisions, there’s a balance to be had. My preference when insulating the frame is to fill the thickness of the timber studs with insulation and add a thinner insulated wrap around the outside – typically of 25mm or so.

Permeability & the cavityAlthough there is much posturing from technical teams about the merits of their systems, one simple principle with timber frame is good to hang on to; and that is the principle of increasing permeability through the panel components. Effectively we are trying to design our panels so that they are airtight and then to control internal moisture within the building from a mechanical ventilation point of view. So we start on the inside of the panel face with the lowest level of vapour permeability, which is usually our polythene vapour control layer (VCL). Then we have our chosen insulation followed by our external sheathing layer and our breather paper wrap. With this principle, if internal moisture does penetrate the VCL then it will find it easier and easier to get through the subsequent layers until it migrates out into our vented cavity where is gets naturally dissipated away. What we don’t want is vapour getting stuck in our panels which then condenses; QED interstitial condensation. |

Model 2

Another consideration with the cavity wrap would also be the lack of permeability of PIR insulation as we are adding this to the outside of our panel’s breather paper. This is to some extent counterintuitive and could cause interstitial condensation between the paper and the insulation.

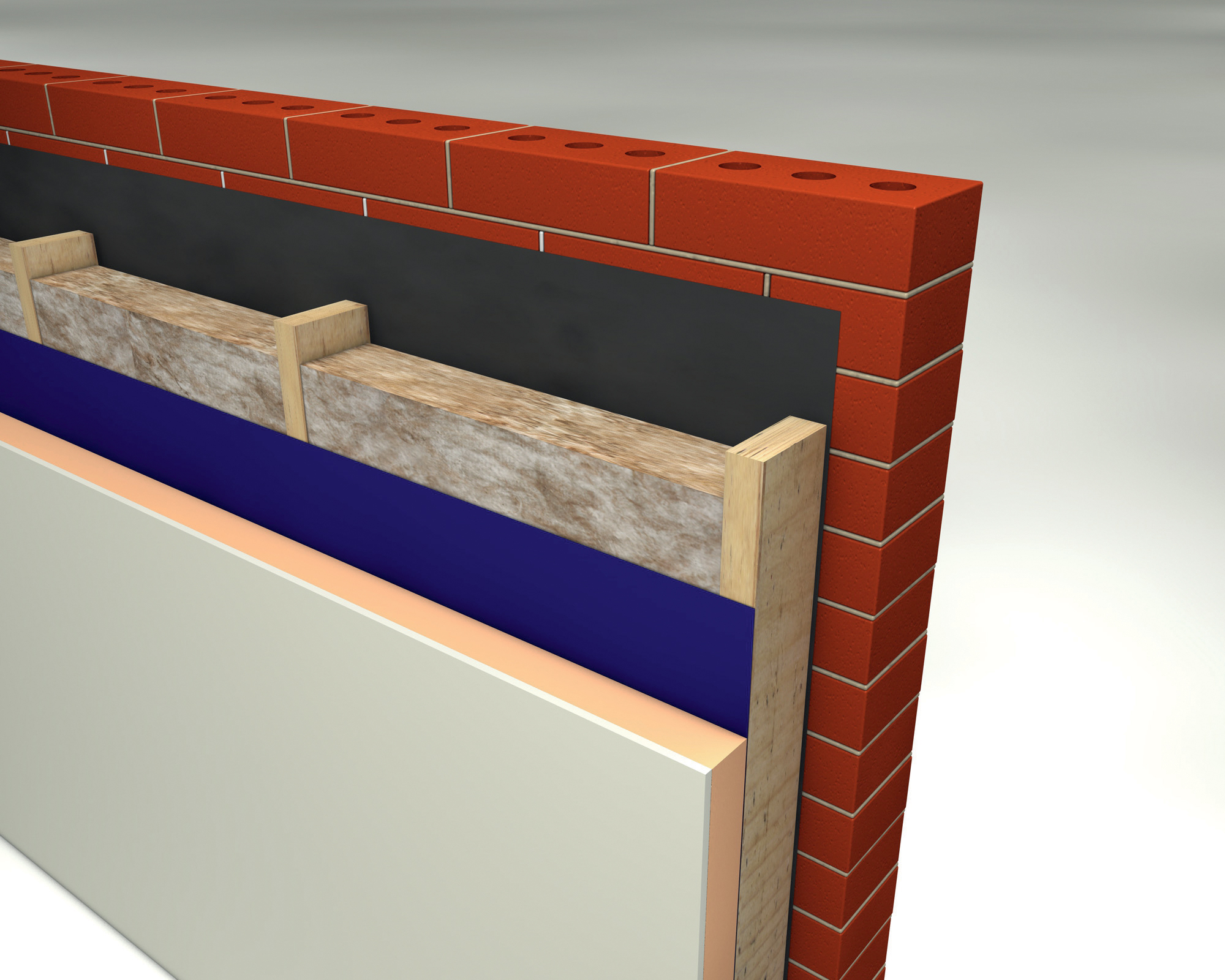

With that in mind, our second generic design option is the conventional core panel, but this time featuring an additional layer of insulation on the inside rather than out. Using an industry manufacturer that specialises in mineral wool insulation with a limited range of PIR laminated plasterboard options, we can get to equally impressive performance standards – although not quite as good as the PIR.

Published data suggests a 140mm thickness of Knauf Earthwool Frametherm 32 between the studs plus 40mm of PIR internally with qualifying plasterboard and vapour control layers (VCL) will achieve a U-value of 0.17 W/m2K when clad externally with brick. However, this does not provide a service zone, so if needed, one would have to be created internally with counterbattening on the warm side of the VCL.

Knauf’s mineral wool panel system, with Knauf Earthwool Frametherm insulation plus an internal layer of PIR laminate; data shows that this can achieve a U-value of 0.17 W/m2K

A recent quote from one of the national merchants for a genuine large order supply puts the current cost of 100mm mineral wool cavity batts at just over £13/m2, versus 100mm top of the range PIR at £25/m2.

There is no logic to insulation pricing, unfortunately, as the manufacturers won’t supply direct and the national merchants get (and offer) competitive volume rates on certain brands and punitively high rates on products that they don’t normally stock. So you’ll have to work the system and get multiple quotes from different suppliers to work out the best combination of deals in your area.

Find more panel systems and insulation products in the Build It Directory

EXPERT VIEW: Benefits of natural insulation in timber constructionBill Keir from Oakwrights gives his top tips on the benefits of natural insulation for panelised timber builds: Built with excellent insulation density, natural insulation panels provide excellent U-values. This improves the thermal performance of the walls and roof of a build, giving significantly improved comfort, lower running costs and energy bills. This is a great starting point for a fabric first approach to a home. Natural insulation panels are designed so walls can breathe and have an excellent decrement delay factor. This allows atmospheric moisture to be absorbed in winter and dry out in summer, avoiding unnecessary moisture build up. This delivers the benefits of traditional, breathable materials in controlled, contemporary construction. An integral benefit of natural insulation panels is the airtightness you are guaranteed. When used in conjunction with Passivhaus-quality sealing tapes, ensures draughts and uncontrolled ventilation are virtually eliminated. Installing a mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) system will provide airtight homes with high-quality fresh air all year round. Oakwrights’ award-winning WrightWall Natural encapsulation system features blown cellulose (the natural fibre of wood) manufactured from recycled newspapers. This is treated against insect infestation and to be fireproof. It is proven to have met rigorous Passivhaus standards, and was used in conjunction with oak to construct the UK’s first certified oak frame Passivhaus home in Yorkshire. Bill Keir is operations director at Oakwrights and has more than 35 years’ experience in the timber frame industry. Oakwrights is a member of the Structural Timber Association (STA). |

Model 3:

A third option is a twin wall system, which effectively uses two thinner core panels, mechanically joined but with limited thermal bridging (see Viking image, previous page). If you’re interested in passive standards then to my mind this is probably the route to go.

These systems can have racking on both the inner and outer faces, providing good structural rigidity, and the space between the twin panels is completely insulated save for the minimum requisite ties to join the two panels together. U-values can get as low as 0.12 W/m2K, but for the ultimate enthusiast this can probably be improved upon.

Building with solid timber panels

One final thought is the conductivity of wood and the principles therefore of cross bridging with timber studs in panels. Timber has a conduction of heat (0.13-0.15 W/mK) which is about five or six times that of the best insulations (0.02-0.03 W/mK). But by comparison wood is about five times less conductive than a clay brick or a dense concrete block.

Notwithstanding this, there is much interest in the use of cross-laminated timber panels in construction, which are essentially solid timber panels. These are usually selected for their remarkable strength. But from a thermal performance point of view they do need an insulation wrap, using any one of the industry options, on either the inside or out (but more likely the out).

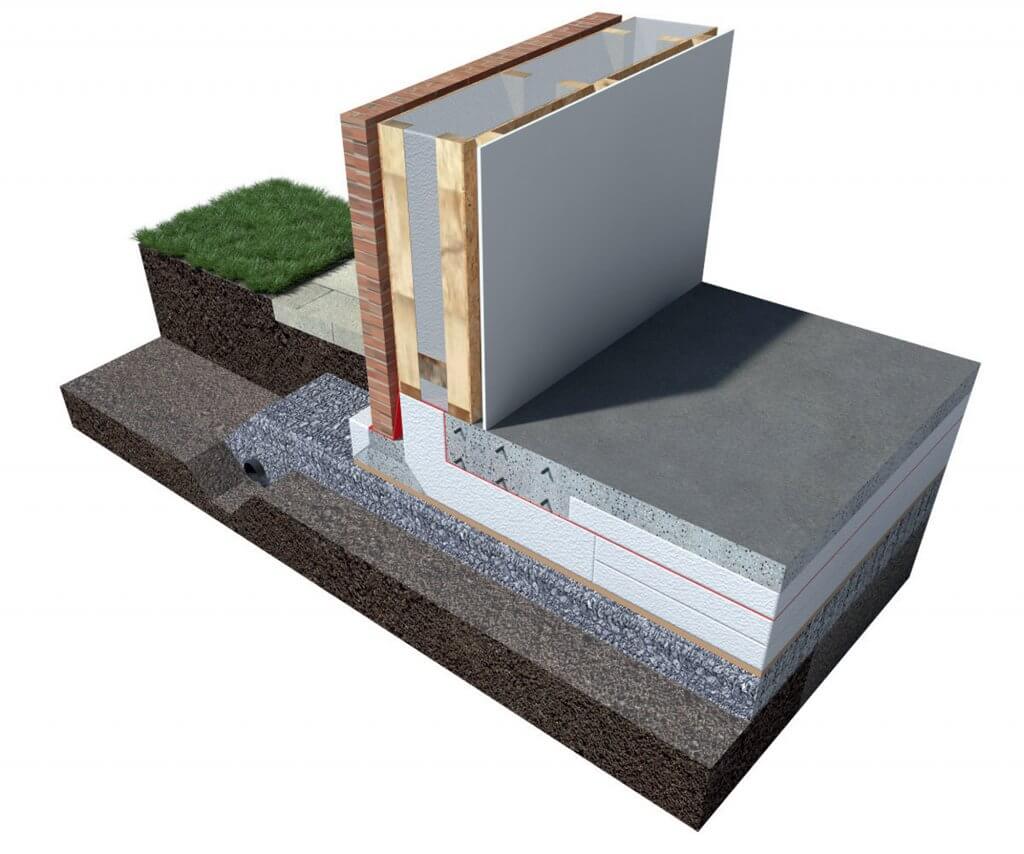

Airtightness: Interfaces at floor & roof junctionsThere is no point in making serious purchasing decisions about a specific panel’s performance unless the same diligence is paid to the interface details of these insulated wall panels to floors and roofs. Therefore, the airtightness of a building must be carefully tested at the end to ensure insulation in difficult-to-access voids is installed with care and that overlaps between VCLs are properly joined and taped. The SAP calculation software has the equivalent of robust details for these interfaces and extra scores are added if you can demonstrate compliance. |

Top image: Knauf’s mineral wool insulation being installed between timber studs. If needed a service void can be battened out

This article was last updated on 20th September 2022

Login/register to save Article for later

Login/register to save Article for later

Hi, really enjoy the clear manner in which you explain certain features and benefits or pitfalls of particular solutions.

what about insulating timber flooring?

have you got an article that addresses this at all?

i have an idea of what to do; on top of 4×2 beams (600) i was going to lay a sandwich of 80mm PIr between 2 sheets of 9mm osb. then finish flooring with a soundproof layer on top (potentially electric ufh as well)

any ideas or a link to an article would be great. we are at planning stage at the moment.

thank you for your time

Hi Nathan,

Thanks for your question.

This feature: https://www.self-build.co.uk/renovating-old-floors/ has information regarding insulating timber flooring which should be of use to you.

This article: https://www.self-build.co.uk/12-golden-rules-timber-flooring/ offers some broader advice on fitting timber flooring (including underfloor heating), and may be a useful tool in general.

Hope this is of help!

I prefer your Model 1 where part of the insulation is in the cavity to avoid cold bridging, but note your point about interstitial moisture build up between paper and insulation. Could this be avoided if this outer insulation layer was kept thinner (you suggest 25mm) AND the OSB3 board and paper were on the CAVITY side of the 25mm insulation sheaf?

The fixings would have to be screwed though the paper, board and 25mm insulation into the frame, of course.

But I did wonder if this would set up another series of permeability problems or would be acceptable? Thankyou – Tim